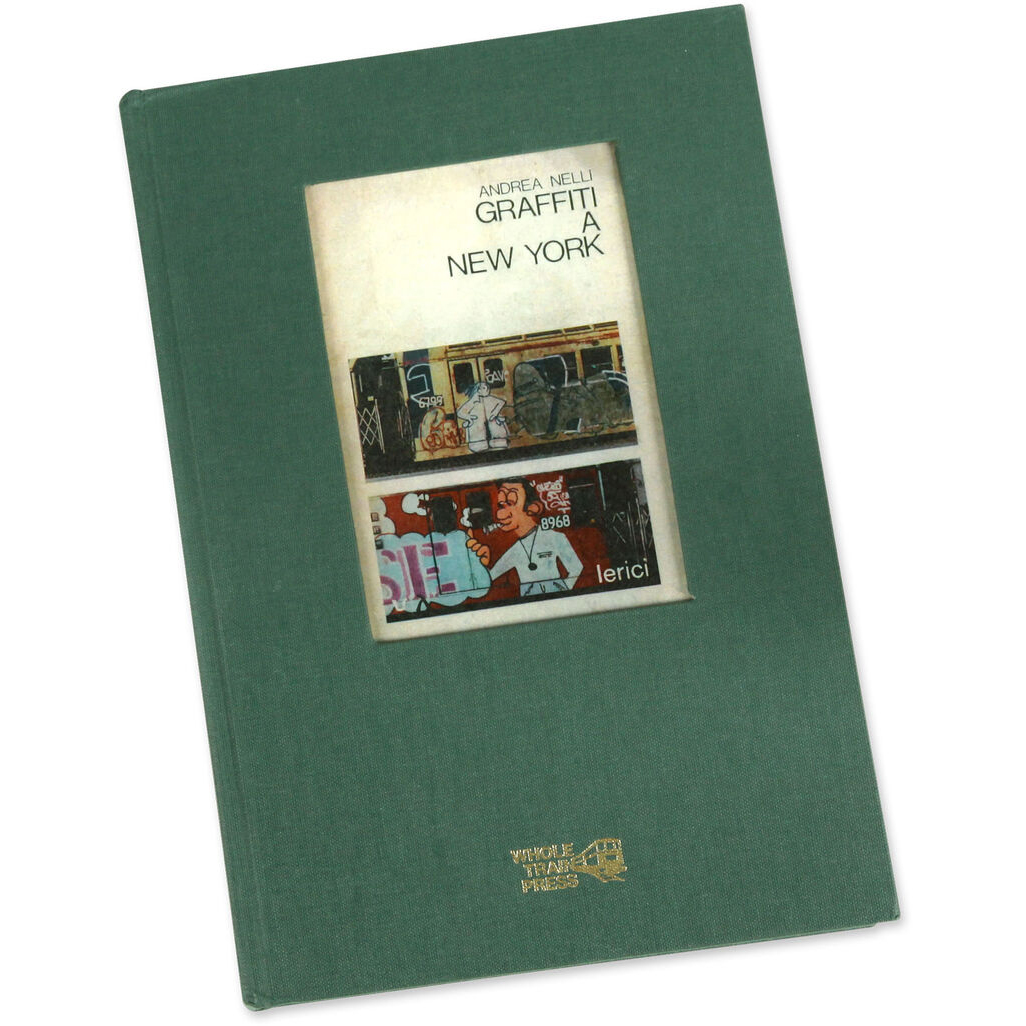

Graffiti A New York

35,00€

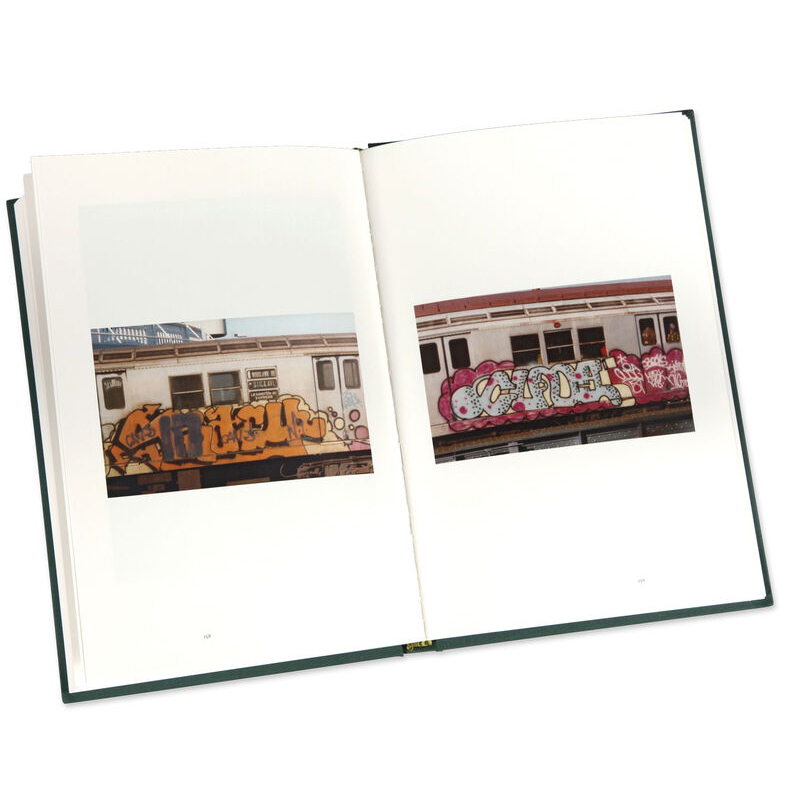

Andrea Nelli was twenty years old when he first went to New York, and he saw BIG-O 116, EVIL ERF 14, RAT FINK 131, SUPER KOOL 223 on the walls. They looked like undecipherable codes, written everywhere with black spray. Afterword he understood that they were always the same names, repeated throughout the city. It was in the early 70’s and all the trains run completely covered by colored and giant graffiti.

The subway and Manhattan walls were covered, too. Andrea started shooting photos, because captured by these compositions and he succeeded in getting in touch with different cliques of writers who introduced him in the New York scene. Big names as COCO 144 guided him.

Still student, Andre Nelli decided to focus his thesis on this just born movement, but already spreading out constantly. More than a 100 photos of names and historical pieces were captured by Andrea, that form a test which presents the phenomenon at its beginning.

Through his work, we get to know a guy with a sour look, who is trying to find his way among names, gangs, walls and subway, tag and through up, to get to the same conclusion that is still valid nowadays 40 years after:

“to get your Name around”. The rule of graffiti.

GRAFFITI A NEW YORK

In 1973, this phenomenon of graffiti runs rampant,

reaching its peak that summer. At the beginning of

the year, the graffiti piece grows in epic proportions. This

innovation is owed to black writers from the Bronx like

SUPER COOL 223, RIFF 70(WORM/CASH), and PHASE 2.

The press defined this new genre as “Grand Design” but the kids called it Top to Bottom or more simply T to B, alluding to the fact that graffiti vertically covers the full height of a subway car. The external of the train is no longer covered with small, monochrome writings of different sizes, but by a single, multi-colored graffiti. Some of these T to B pieces are so elaborate and complex in form that the New York Times puts forth the hypothesis that they are products of a collaboration between professional artists and graffiti writers. In February of 1973, the Boy Scouts form an ecological program that attempts, in vain, to diminish the amount of graffiti by sending out teams of cleaners. In January and February of the same year,

the police perform 282 arrests. Still, the record shows two favorable interventions in graffiti art. The first is by an unknown artist in search of publicity, Tazio D’Allegro, who associates graffiti to urban waste and the aesthetics of “slop art,” a sort of pop art that shifts the lens from the consumer to waste. The second intervention is by P. R. Paterson who sees graffiti as a spontaneous protest against the bureaucracy of the subway. On March 26th, 1973, New York Magazine publishes an article by Goldstein that, in my view, discusses for the first time a series of interpretations of the phenomenon.

Goldstein announces that graffiti is the first authentic youth culture born on the streets since rock’n’roll in the 1950’s. In the same issue of the magazine, painter Claes Oldenburg comments:

“You are in a grey and sad subway station when all the sudden a graffiti train breaks, bringing with it the light of a bunch of tropical flowers. You think: it’s anarchy, and you ask yourself if trains will keep working. But then you get used to it”. The same issue of the New York Magazine depicts the winning graffiti of the “Taki Award”, an award organized by journalists for graffiti writers. Thus, a trend is emerging. It is significant that the journalist’s choices for the award fall upon two writers, SPIN and STOP, who the kids call toys, or amateurs.

Esgotat